Human Rights & Democracy

Documenting the Journeys of Women Working for a Better Reality

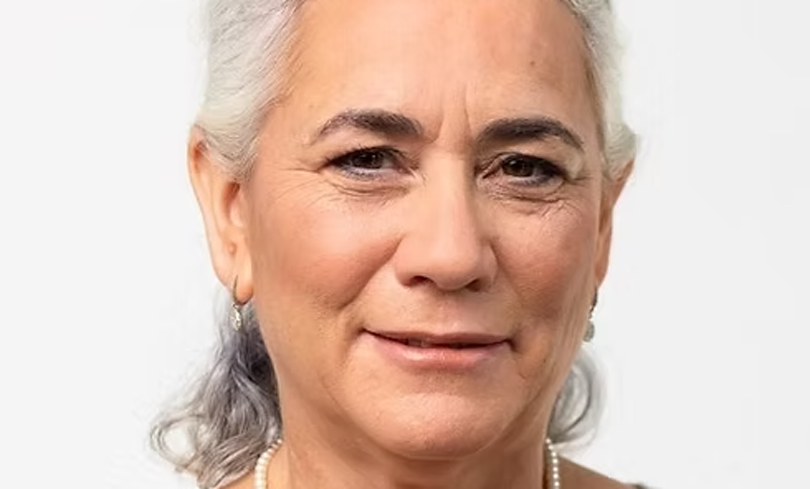

Photo Credit: Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages

Inspired by the memory of Vivian Silver, a long-time peace activist who was murdered on October 7, 2023, a group of interviewers led by activists Ghadir Hani and Dror Rubin came together to document the life stories of 21 women, Jewish and Arab, each working in her own way to reshape reality.

Guided by Professor Amia Lieblich, the group wove these stories into a remarkable book, Women Write Hope. Two weeks ago, we brought you an interview by Galit Pnina Avinoam with Rula Daood, national co-director of NIF grantee, Standing Together, and a Palestinian citizen of Israel. This week we are featuring the story of Dr. Yeela Raanan, Executive Director of the Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages, another NIF grantee, who was interviewed by Mimi Shefer.

To read the rest of this inspiring collection, you can purchase the book here.

Yeela’s Story: The Politics of Love

Interviewed by: Mimi Shefer

Dr. Yeela Raanan is the Executive Director of the Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages. She also works as a lecturer at Sapir Academic College, is a member of Kibbutz Kissufim in the western Negev, and is an activist for peace and justice

—

Yeela greets me at a side entrance to a luxurious villa in Omer and leads me into a small apartment—a refuge from her first refuge—a hotel at the Dead Sea. She expects to move into a further refuge—a trailer park. Her original home (from which she still needs refuge) is in Kissufim in the Gaza Envelope – the term used in Israel for the communities in the western Negev close to the border with the Gaza Strip. Her soft, blond curls gleam in the Negev sun, contrasting starkly with her dark, gentle eyes. These eyes have seen some unimaginable sights but are not devoid of the practicality and decisiveness I heard in her voice on the phone. Equipped with water, we set off. I encourage her to present her personal chronology.

I live in the Gaza Envelope and have experienced all the Gaza wars. In Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009), my eldest son fought in Gaza. They asked me to speak out in the media against the war, and my statement then was very clear: “I will continue to live on the border. This is my home.” How can a war create good relations with neighbors? Sometimes, there may be no alternative. But have we really examined all the possible solutions? After all, we will continue to live side by side in the future, and it is clear to me that we have not tried. I remember Operation Cast Lead. I call it the First Gaza War. The most difficult experience for me in that war was when a missile fell on the soccer field in our moshav. My son was playing with his friends on the field. Somehow, all four of them were not injured. But on the other side of the street, shrapnel entered the homes of the Thai workers and injured them.

Her thoughts wander elsewhere and then her dark, soft eyes return to me.

The next war I experienced was Operation Protective Edge. Women in Kibbutz Tzuba near Jerusalem hosted us; only the women and children moved there. I’d listen to the news and all I would hear were men discussing and leading the war. Yet we are responsible for the children—for life. I think about the mothers on the other side of the border too, and it is clear to me that there, too, the women’s world and the men’s world are separate. The men’s world manages the war and the women’s world preserves life. Toward the end of the war, I saw an advertisement for Women Wage Peace. I immediately felt a connection and joined the

Movement. I remember entering a tent they set up called Tzom Eitan (“Protective Fast”). I felt that the Divine Presence was resting there. It was an amazing experience.

Tell me a little about yourself. What sparked your activism?

I was born to Ashkenazi parents. My father was born in Brazil. He came to Israel at the age of nine. My mother was born in New Zealand, and she came here when she was 17. I was born in Kibbutz Ein Yahav. We traveled to New Zealand, where my father continued his studies. By the time we came back to Arad, where I grew up, I already spoke English. It’s interesting that even today people ask me: “What passport do you have?” And I reply: “I have an Israeli passport, that’s what I have.” My first marriage was to a man from Arad. We went to the United States for the first time when the army sent him there. Shortly after we returned to Israel, my mother passed away. Our two eldest sons were born here, and then we traveled to the United States again. We got divorced there, and I returned to Israel alone, with my three sons, back to Lehavim. Years later, I met my second husband, who is from Kibbutz Be’eri. Our youngest daughter was born just before we settled in Kissufim; she’s 13 now.

Even as a teenager, I had a strong sense of justice. I grew up in a left-wing Zionist family. My mother took me to a parlor meeting with Shulamit Aloni. My father was a Rabin supporter, closer to the center. Zionism was a very significant part of the way I grew up. I’ve changed over the years—not in leaps, but through a long and painful process.

I started my bachelor’s degree in the United States and completed a degree in pure mathematics after we returned to Israel. My mother was 45 when she died. I left out one important detail. My brother was exactly one year older than me. He died by suicide when he was 18, during his military service. It was on the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day. It killed my mother: she got cancer, and six years later she was no longer with us. She died three days after my eldest son was born. All this pain mixed together. These are hard blows at a young age.

Both of my parents were born to parents who fled from war. Their parents survived, but over a hundred of their relatives were murdered. As a result, my parents carried some serious emotional scars, and they passed them on to us. I’m the eldest daughter, and I was the object of my mother’s anger for what she suffered from her own mother and grandmother. In the end, I turned what I suffered into positive energy. I took lemons and made lemonade

Tell me about some of the milestones in your process of change.

When I was studying for my master’s degree in contemporary Judaism, I felt a need inside me to do something for society. I worked as a group counselor in Zionist-Jewish educational programs, and there I met many young Jews from Israel and abroad. One of the things that shocked me was when we talked about democracy and Israel. I asked Israeli high school students whether Israel is democratic. They replied: “Of course!” I said: “Great! But what about the millions of people we control without giving them the opportunity to decide what will happen to them?” For these students, this condition didn’t change the fact that Israel is a democracy. But for me it was a glaring contradiction! While I was in the United States, I studied at the University of Utah. The lecturer who influenced me the most was an Israeli of Iraqi origin, Ruth Tsoffar. One of her courses offered a very critical analysis of the memory of the Holocaust in Zionism. Suddenly, I had to confront criticism regarding essential parts of my beliefs. I was really angry with her at first. But it was a process of relearning. And I had Palestinian friends, because it is possible there.

We were four women friends and we called ourselves the witches. The ability to look at our lives and our society with love and criticism simultaneously was a tremendous gift. This contrasts with Israel today, where criticism is always interpreted as aggression.

When the time came to do research for my doctorate, it was clear to me that I would do it among Palestinian citizens of Israel. Ruth Tsoffar, who has been the most important mentor

in my life, said to me: “Ask to work as a schoolteacher within an Arab community in Israel.” For a whole year I worked in Jadeidi-Makr, and it was one of the most beautiful years of my life. I came with my three children, and we lived in a nearby kibbutz. Until then, I had only experienced a brief acquaintance with the Bedouin population in the Negev. When I was 17, still in the year of mourning for my brother, I worked at the veterinary hospital near Tel Sheva. There was a young man of 20 named Izzat Abu Rabia and a geeky Canadian guy with an earring. After Izzat and I became friends, they invited me and my father to their home. That was the only time I visited a Bedouin community until I finished my doctorate.

Before I returned to Israel with my sons, I was accepted as a lecturer at Ben-Gurion University, and after I arrived, I was taken on as coordinator of the Forum for Coexistence in the Negev. This was the first time I had visited the unrecognized villages, and I was in shock. How could I grow up here without knowing that all this existed?!

What do you feel and think today?

The main question I ask myself and other people is whether we consider ourselves equal to others and not better than them. That’s the mindset I adopted when I started working at the Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages, where I still work today. As Israeli Jews, we are educated to assume that as Westerners, we know more. The process of disillusionment is painful and takes time, because you have to dismantle a deeply entrenched belief. Everything that seems obvious and natural is shattered into pieces. Despite the suffering, I was willing to go through the process and, in the end, I came to understand that my partners’ knowledge and way of thinking are equal in value to mine. I am grateful for the trust that Bedouin Arab citizens and residents in the Negev place in me. I think this trust has two foundations. Firstly, I am willing to work hard to help them build a better future, and secondly, I never feel that my Jewishness, my Westernness, or my doctorate make me better than them in any way.

The main message that has emerged in Israel during the war is “We will win together!” From the first time I saw this slogan, I wondered—who is together? Who is together with me? Who does “we” refer to? Are my Arab friends and colleagues Atiyeh, Suleiman, and Laila part of this “together”? It’s very clear to me that the slogan doesn’t include them. And as a result, it doesn’t speak to me at all. My world is not a world of Jews and Arabs. My world is a world of human beings.

What happened to you on October 7?

I was in the United States with my youngest daughter Shani and we returned to Kissufim on October 6. At 6:30 the next morning, I woke up to a “Code Red” alert and rushed over to her room, which is also our house’s safe room. We locked ourselves in the safe room and everything went crazy. I realized that I had left my phone in my bedroom, and it bothered me. We sent messages on the family WhatsApp group from Shani’s phone because beside us, two of my sons also live on the border. From a young age, I always taught them to let me know that they’re okay.

It’s hard for me to relive this. I don’t remember it all. I only know that we heard a lot of small arms fire, apart from the rockets. It was a completely different noise from anything I’d ever heard before. Then we realized that the door handle on the other side had fallen on the floor. We couldn’t get out of the safe room and I didn’t have my phone. That’s not a good combination. I opened the window to jump out. On the dirt path, I saw a car driving quickly, and in the front window there was a guy in army uniform with a drawn rifle. I thought to myself: “What happened to our soldiers? They’ve gone crazy!” It later turned out that these were Hamas Nukhba operatives, dressed in Israeli army uniforms. Later, we moved to the second safe room. I had my phone with me now, and I even made coffee in the middle of everything.

But most of the time we stayed locked up in the room. Occasionally we’d go out to the bathroom or to get something. I turned on the TV, but after a minute I realized that it would probably traumatize Shani even more, so I turned it off.

Then terrorists entered our house, making a crazy noise. They hit the front door with a hammer, even though it was open, and they shot at the window. After they came inside, they smashed cabinets, threw glass bottles from the refrigerator onto the floor, and overturned wine bottles from the cabinet. They pulled out Tomer’s office drawer and scattered the folders everywhere. All this time, Shani and I stayed in the safe room, whispering and hugging each other as we lay on the bed. Shani asked tough questions: “Mom, will they kill us?” “Maybe,” I replied. I was shaking and I couldn’t understand how she didn’t see. But she went on asking questions. I realized that I needed to calm her down and give her the feeling that everything would be okay. I said to her: “Listen, I’ll talk to them in Arabic, and I’ll tell them that I’m one of the good guys.” They murdered many good people who worked for peace that day. I knew it didn’t mean

anything, but Shani was only 12, she didn’t know that.

Then they left. I still didn’t think they had come to burn and murder. It was only later that I slowly began to understand. I wanted to find my younger son, who also lives in Kibbutz Kissufim. His house is a five-minute walk from my place. I messaged the kibbutz security coordinator and asked him to check on my son, but no one did. They messaged me: “You don’t understand what’s happening here! There’s a war going on.” It’s true—I didn’t grasp it. I wrote to them: “I’m going to look for my son. I’m leaving Shani alone at home, please take care of her.” When I went outside, it finally struck me. What were the chances that I would reach him and return back alive? So I went back to Shani. At least I was alive with her.

Around 5:00 PM, the soldiers arrived. I heard them and went out to them. “Stay here! Go back into the safe room.” These were IDF soldiers but they looked totally lost. At midnight, my daughter said to me: “Mom, enough, I’m tired! Let’s get out of here already!” We opened a drawer where we kept all the keys, but it was empty. I looked outside and saw that my car was gone. I said to Shani: “We’re stuck here until someone else gets us out.” At 6:30 in the morning, soldiers came again. I went out and said, “Get us out of here!” They told me to grab a bag and come, and they took us outside the kibbutz fence. Suddenly we were in a different world. It was calm there, with soldiers and buses. And inside the kibbutz—war.

How do you feel today?

I want to go home. I don’t care about myself. But there are two other issues to consider. Firstly, I’m responsible for Shani, and secondly, I want my grandchildren to visit me, at least sometimes. Will they come to the kibbutz if it is so dangerous?

Deep inside, I’m very frustrated. I know that we could have made peace and this place wouldn’t be dangerous. We could have done it 20 years ago or 30 years ago. But our country chooses to make me live in a dangerous place because of its need for supremacy and power, and because of irrational fears and an inability to connect to other people’s humanity. I want to go home but I take my responsibility toward Shani very seriously.

In what ways have you changed?

First of all, my longing for peace has increased. It was clear to me before that peace is the way, but it’s even clearer to me now. After all, we have been trying the other way all day and every day since Rabin’s assassination. So, let’s deconstruct this desire to harm the other. Secondly, I have lost a lot of my joy in life, my optimism and faith in humanity. I really hope I can get it back.

I can see where Israel is going. I have already lost the right to teach many courses because of what people write about me on the internet. For right-wingers, the most dangerous people are those who are willing to speak gently and calmly, and with love, out of a desire to create something positive. Other people may listen to them and that’s the worst thing for the right wing. There are right-wing campaigns against me on the internet, and I can no longer make a living as I once did. This also shows that the academic world, where I work, is already surrendering to the campaign to silence critics. For sure, I am afraid of what is happening to Israel.

I’m also deeply invested in my peace-making work. I work most of the day together with the residents of the unrecognized villages. Israel is refusing to recognize these villages and force Bedouin Arab citizens of the Negev to move to the Bedouin towns so their land may be seized. This policy is part of the system. My ability to be the Bedouins’ partner helps me stay sane.

My last question touches on something you just mentioned. You talk about the politics of love. But you’ve also described the personal hatred that your activity arouses. How can peace and hatred be so close?

Yeela answers fluently, cutting the air with her hands to emphasize her words. I imagine her moving smoothly from the double bed where we are both sitting to a lecture podium as she offers comprehensive explanations for complex human processes.

Let’s go back for a moment to the Rabin era. After the Rabin assassination, there was a wave of terror attacks. You may ask how Palestinians could blow up buses just before a peace agreement. The reason is that some Palestinians cannot accept an agreement that divides the country, instead of declaring that it is all Palestinian. For them, it’s all theirs. Meanwhile, Smotrich and Ben Gvir are driven by a feeling of superiority, certain that God has chosen us from all the nations. So the whole land is theirs. It’s a self-perpetuating vicious circle.

When someone raises the logic and politics of love or of peace in general, it clashes with this idea. The discourse of peace pulls the rug out from under their feet, because the essence of peace is about sharing. When the peace camp meets the other camp, it is still expected to uphold the values of peace, and therefore it does not hate or harm the other camp. In contrast, when the peace camp succeeds, the other group which is grounded in violence, supremacy, and control, feels attacked.

I remark to Yeela that Israelis talk about meaningful military service, while what she is doing is a different kind of service. “Meaningful human service,” she suggests.

After a long hug, I go out into the Negev sun. I leave with some painful insights about the most extreme moments of life, as well as a fistful of hope that it is still possible to believe in humanity and in the politics of love.